Since I can't seem to get myself to write an all out, well-constructed post while I'm on vacation, I thought I'd point readers to this Op-Ed in the NYTimes.

It's one of those thingys where the Times publishes an Op-Ed piece, and then asks for readers' responses, which it publishes on Sunday, with a response by the original author.

This one is about Obamacare, and the Affordable Care Act, and how the exchanges set up to help people find coverage are wonderful, and how could those evil Republicans oppose this, and there are many examples of this system working, etc. (I'm a registered Democrat, BTW).

Most of it fell out on the side of: the ACA is going to have a rocky start, but in the long run it'll be great because everyone will have access to health insurance.

I really don't know how the ACA is going to play out. Maybe it'll really help people get insurance coverage. What struck me, though, is the way everyone is all excited about health insurance, and no one is talking about health care.

Yay! Everyone will have access to health insurance. Boo! Many doctors won't accept the insurance because of the Byzantine bureaucracy and the paltry reimbursement. Boo! Doctors who do accept insurance will be bombarded by overwhelming numbers of patients with shiny new health plans.

Coverage is not synonymous with Care.

Welcome!

Welcome to my blog, a place to explore and learn about the experience of running a psychiatric practice. I post about things that I find useful to know or think about. So, enjoy, and let me know what you think.

Sunday, August 25, 2013

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

No Lemonade in Sight

I just finished reading an article entitled, Trading in the Obamacare Lemon.

It's interesting, so I thought I'd post a link.

I'm still too deep in vacation mode to write up anything more cogent about it.

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Ah, Vacation

I feel a little sheepish about this, but yes, I'm writing a post while on vacation. That wasn't my intention. I went off to an indulgent, overpriced spa to be indulged and not think about anything but being indulged. But part of the pleasure of vacation for me is that I get to catch up on back-issues of magazines that have been lying around, beckoning to me, for months.

Well. I was working my way through the October 2012 issue of Metropolis, the theme of which is "Brave new City: Seven Visionary Teams Re-imagine the Urban Experience". And I found this:

It's the HomeWerk table and chairs by LUNAR, a system designed for working from home. Those are not cardboard figures sitting in the chairs. The chairs, themselves, are dynamic screens.

These digitally sophisticated furnishings fit easily into most homes and apartments by replacing the traditional dining set with display backs that allow for life-size, face-to-face meetings with coworkers, customers and clients.

You sit in your chair at home, and participate in a meeting at work. When you move, your 2D persona moves. When you speak, it speaks. Oh, and it doesn't matter if you're in your underwear.

"The real-time video allows [users] to wear whatever they want, as their screen double displays appropriate business attire."

(Not sure why "glasses" isn't lifting his left hand in the photo)

You can change the appearance of the furniture, too, so when you're finished working in your modern "office", you can go home to your Victorian, or country cottage, or beach house, or groovy pad.

Think of the applications outside of an office meeting! You can have Thanksgiving dinner with your daughter in Chicago and your son in Hong Kong!

Aaaaaaand...You can have therapy sessions with patients. This is SO much better than Skype. And it brings up all sorts of interesting therapeutic issues.

For instance, you learn a lot from the way a patient chooses to dress to a session. What are you missing if you have no idea what the patient is really wearing? What do you learn from the clothes the patient chooses to display? What about what you're wearing?

Would you and your patient need to own the same piece of furniture? What would that be like? Is it different from both of you owning computers?

There's also something called, "impactful time-shifted video messages", which allows users to join meetings even if they have schedule conflicts. I don't understand how that would work. Sounds like time travel. What would that mean for missed sessions? Gives me a headache to think about it.

Of course, even with the coolness factor, there's still a lot missing. Odors, room temperature, everything that goes with physical presence. And I don't believe HomeWerk is in production. But that just means there's more time to work out the details.

Well. I was working my way through the October 2012 issue of Metropolis, the theme of which is "Brave new City: Seven Visionary Teams Re-imagine the Urban Experience". And I found this:

It's the HomeWerk table and chairs by LUNAR, a system designed for working from home. Those are not cardboard figures sitting in the chairs. The chairs, themselves, are dynamic screens.

These digitally sophisticated furnishings fit easily into most homes and apartments by replacing the traditional dining set with display backs that allow for life-size, face-to-face meetings with coworkers, customers and clients.

You sit in your chair at home, and participate in a meeting at work. When you move, your 2D persona moves. When you speak, it speaks. Oh, and it doesn't matter if you're in your underwear.

"The real-time video allows [users] to wear whatever they want, as their screen double displays appropriate business attire."

(Not sure why "glasses" isn't lifting his left hand in the photo)

You can change the appearance of the furniture, too, so when you're finished working in your modern "office", you can go home to your Victorian, or country cottage, or beach house, or groovy pad.

Aaaaaaand...You can have therapy sessions with patients. This is SO much better than Skype. And it brings up all sorts of interesting therapeutic issues.

For instance, you learn a lot from the way a patient chooses to dress to a session. What are you missing if you have no idea what the patient is really wearing? What do you learn from the clothes the patient chooses to display? What about what you're wearing?

Would you and your patient need to own the same piece of furniture? What would that be like? Is it different from both of you owning computers?

There's also something called, "impactful time-shifted video messages", which allows users to join meetings even if they have schedule conflicts. I don't understand how that would work. Sounds like time travel. What would that mean for missed sessions? Gives me a headache to think about it.

Of course, even with the coolness factor, there's still a lot missing. Odors, room temperature, everything that goes with physical presence. And I don't believe HomeWerk is in production. But that just means there's more time to work out the details.

Thursday, August 8, 2013

Lifelong Learning-A New Frontier

This post is tangentially about Maintenance of Certification (MOC). So before I get to the main point, I want to refer readers to Jim Amos' blog, The Practical Psychosomaticist. The link will take you to a form letter to oppose MOC and MOL (Maintenance of Licensure). Dr. Amos generously gives me top credit for it, but it's actually a letter he sent to the AMA and APA, that I modified to make it convenient for other people to use.

Check it out, consider how you feel about MOC and MOL, and if you're so inclined, mail it off.

I've already written about my feelings regarding MOC. So let's get to the main topic, Lifelong Learning. Let's assume the world suddenly becomes a sensible place, and the inane requirements for MOC are done away with. No expensive recertification exam, no dumb PIPs, no useless CME credits. I still consider it my obligation to stay current, so I can take better care of my patients.

What I do now, and would probably continue to do in the aforementioned utopia, is subscribe to The Carlat Report and UpToDate. The Carlat Report doesn't take money from drug companies or other sponsors. And UpToDate is just an excellent resource all around. And no, they're not paying me to write this. (Full Disclosure: I was paid by The Carlat Report for my article in their May edition, but that's the extent of my financial relationship with them).

I've also recently subscribed to NEJM's Journal Watch Psychiatry, but I'm just testing it out at this point, so I can't comment.

But here's a new idea. Or maybe it isn't new, but I don't know about it:

Online Journal Club!

It's the kind of thing that LinkedIn and Facebook lend themselves to. Post a free article online, maybe once a week, allow some time for people to read it, and then ask people to write in and discuss it.

People could suggest articles, and vote on which one they want to read next. And it's free. And collaborative. And the kind of thing I tried to do with my residents, back when I was a unit chief.

A book club would work, too, but that would involve a purchase.

There are all kinds of online learning resources:

MIT's OpenCourseWare

MIT and Harvard's EdX

The Khan Academy

Why not, The Psychiatry Collaboration?

I'd love for readers to comment on this post. Let me know what kind of lifelong learning works for you. Where do you go to stay current? Would you participate in a free online journal club?

How about this article:

A Rating Scale for Depression, by Max Hamilton

J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1960, 23, 56.

I found the link to it on the BMJ site. I've never read it before, and sure, it's from 1960, but it might be interesting and fun to read about the early development of the HAM-D.

Check it out, consider how you feel about MOC and MOL, and if you're so inclined, mail it off.

I've already written about my feelings regarding MOC. So let's get to the main topic, Lifelong Learning. Let's assume the world suddenly becomes a sensible place, and the inane requirements for MOC are done away with. No expensive recertification exam, no dumb PIPs, no useless CME credits. I still consider it my obligation to stay current, so I can take better care of my patients.

What I do now, and would probably continue to do in the aforementioned utopia, is subscribe to The Carlat Report and UpToDate. The Carlat Report doesn't take money from drug companies or other sponsors. And UpToDate is just an excellent resource all around. And no, they're not paying me to write this. (Full Disclosure: I was paid by The Carlat Report for my article in their May edition, but that's the extent of my financial relationship with them).

I've also recently subscribed to NEJM's Journal Watch Psychiatry, but I'm just testing it out at this point, so I can't comment.

But here's a new idea. Or maybe it isn't new, but I don't know about it:

Online Journal Club!

It's the kind of thing that LinkedIn and Facebook lend themselves to. Post a free article online, maybe once a week, allow some time for people to read it, and then ask people to write in and discuss it.

People could suggest articles, and vote on which one they want to read next. And it's free. And collaborative. And the kind of thing I tried to do with my residents, back when I was a unit chief.

A book club would work, too, but that would involve a purchase.

There are all kinds of online learning resources:

MIT's OpenCourseWare

MIT and Harvard's EdX

The Khan Academy

Why not, The Psychiatry Collaboration?

I'd love for readers to comment on this post. Let me know what kind of lifelong learning works for you. Where do you go to stay current? Would you participate in a free online journal club?

How about this article:

A Rating Scale for Depression, by Max Hamilton

J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1960, 23, 56.

I found the link to it on the BMJ site. I've never read it before, and sure, it's from 1960, but it might be interesting and fun to read about the early development of the HAM-D.

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

My Counter-Argument

I read this on Pharma Gossip, and it made me angry. According to a new report by Public Citizen, the

"Continued Decline [in medical malpractice payments] Debunks Theory That Litigation Is to Blame for Soaring Health Care Costs."

Some key points:

-The number of malpractice payments on behalf of doctors (9,379) was the lowest on record, falling for the ninth consecutive year;

- The value of payments made on behalf of doctors ($3.1 billion) was the lowest on record if adjusted for inflation. In unadjusted dollars, payments fell for the ninth straight year and were at their lowest level since 1998;

- More than four-fifths of medical malpractice awards compensated for death, catastrophic harm or serious permanent injuries – countering the claim that medical malpractice litigation is “frivolous”;

- Medical malpractice payments’ share of the nation’s health care bill was the lowest on record, falling to about one-tenth of 1 percent (0.11 percent) of national health care costs;

- Medical liability insurance premiums, a broad measure that takes into account defense litigation costs and other factors as well as actual payments, fell to 0.36 of 1 percent of health care costs, the lowest level in the past decade.

Now, I suspect that no one cause is to blame for soaring health care costs. But when I read this:

“The facts clearly and obviously refute the contentions that...malpractice litigation significantly influences health care costs. Medical malpractice payments continue to fall and health care costs continue to rise. It doesn’t take a math whiz to determine that they are not correlated,” said Lisa Gilbert, director of Public Citizen’s Congress Watch division.

I got seriously mad. I thought, "If physicians are practicing more defensive medicine, then it follows that there will be fewer malpractice suits, fewer malpractice payments, and the cost of liability insurance will go down. But more defensive medicine means more tests, means more expense, so the cost of healthcare will increase." Which is what they found.

They're claiming that, "More than four-fifths of medical malpractice awards compensated for death, catastrophic harm or serious permanent injuries – countering the claim that medical malpractice litigation is 'frivolous'."

This does not imply that "frivolous" suits were not brought, wasting valuable time and money, merely that they weren't successful.

I decided to be level-headed about it, and read the report. Well, it's too damn long.

But there's nothing in the report about the number of malpractice suits brought, frivolous or otherwise (at least not to my perusal). Just a lot of figures about malpractice payments.

And I did find the section that discussed the issue of defensive medicine:

In a given snapshot of time, the defensive medicine theory defies conclusive evaluation because it ultimately rests on divining the private thoughts underlying doctors’ decisions. But broad trends over time provide convincing evidence that the defensive medicine theory is essentially bogus. If litigation fears truly prompt unnecessary tests and procedures, then the volume of care rendered should be declining in sync with diminished litigation risk. This thinking is at the heart of the argument for imposing caps on malpractice awards. But, as illustrated above, costs have marched upward while litigation risk has declined. Increased volume of care, including testing, is almost certainly a key reason for the increased costs.

This idea that the volume of care would decrease has to do with the fact that Texas enacted restricted litigation laws in 2003, and that while malpractice payments fell between 2003 and 2010, health care costs increased faster than the national average, especially for medicare diagnostic tests.

Well, maybe. But Texas is not solely responsible for soaring health costs.

So what DOES the report think may be the cause of rising costs?

Those truly looking to stem health care costs should look elsewhere. This report reviews the 2003 and 2013 pay for physicians in six specialties (Anesthesiology, Cardiology (noninvasive), General Surgery, Internal Medicine, Ob-Gyn and Radiology) as chronicled by Modern Healthcare in its annual doctors’ compensation survey. Practitioners of these specialties have seen their pay rise from 24.3 percent (ob-gyn) to 82 percent (radiology) over this time period. For all specialties but one, pay raises have exceeded inflation. Likewise, Modern Healthcare reports that compensation for health care system CEOs rose at more than twice the rate of inflation from 2003 to 2012 (to over $1.1 million annually, on average). Pay increases for chief medical officers and chief financial officers also far outpaced inflation. These figures suggest that financial incentives, not litigation or the fear of it, provide a far more plausible explanation for soaring costs.

You got me. I'm a greedy doctor, more interested in being out on my expensive yacht than taking care of patients.

Here's another set of figures:

WASHINGTON, D.C. Aug. 11, 2010 - Health Care for America Now (HCAN), the 1,000-member coalition that led the successful fight for health reform, released a report today showing that in 2009, ...chief executives of the 10 largest for-profit health insurance companies collected total pay of $228.1 million, up from $85.5 million the year before. The CEOs of UnitedHealth Group, WellPoint, Aetna, CIGNA, Humana, Coventry Health Care, Health Net, Amerigroup, Centene and Universal American took $944.1 million in compensation from 2000 through 2009, according to the report, entitled "Breaking the Bank."

The boldface is mine. But 228 MILLION! That's 3 orders of magnitude greater than the average physician's income. That's the kind of number that would go a long way towards defraying health care costs.

And who is "Public Citizen"? The Board of Directors includes a bunch of lawyers, a couple activists, and one stand-up comic.

I really hope they asked at least one doctor's opinion about medical malpractice.

"Continued Decline [in medical malpractice payments] Debunks Theory That Litigation Is to Blame for Soaring Health Care Costs."

Some key points:

-The number of malpractice payments on behalf of doctors (9,379) was the lowest on record, falling for the ninth consecutive year;

- The value of payments made on behalf of doctors ($3.1 billion) was the lowest on record if adjusted for inflation. In unadjusted dollars, payments fell for the ninth straight year and were at their lowest level since 1998;

- More than four-fifths of medical malpractice awards compensated for death, catastrophic harm or serious permanent injuries – countering the claim that medical malpractice litigation is “frivolous”;

- Medical malpractice payments’ share of the nation’s health care bill was the lowest on record, falling to about one-tenth of 1 percent (0.11 percent) of national health care costs;

- Medical liability insurance premiums, a broad measure that takes into account defense litigation costs and other factors as well as actual payments, fell to 0.36 of 1 percent of health care costs, the lowest level in the past decade.

Now, I suspect that no one cause is to blame for soaring health care costs. But when I read this:

“The facts clearly and obviously refute the contentions that...malpractice litigation significantly influences health care costs. Medical malpractice payments continue to fall and health care costs continue to rise. It doesn’t take a math whiz to determine that they are not correlated,” said Lisa Gilbert, director of Public Citizen’s Congress Watch division.

I got seriously mad. I thought, "If physicians are practicing more defensive medicine, then it follows that there will be fewer malpractice suits, fewer malpractice payments, and the cost of liability insurance will go down. But more defensive medicine means more tests, means more expense, so the cost of healthcare will increase." Which is what they found.

They're claiming that, "More than four-fifths of medical malpractice awards compensated for death, catastrophic harm or serious permanent injuries – countering the claim that medical malpractice litigation is 'frivolous'."

This does not imply that "frivolous" suits were not brought, wasting valuable time and money, merely that they weren't successful.

I decided to be level-headed about it, and read the report. Well, it's too damn long.

But there's nothing in the report about the number of malpractice suits brought, frivolous or otherwise (at least not to my perusal). Just a lot of figures about malpractice payments.

And I did find the section that discussed the issue of defensive medicine:

In a given snapshot of time, the defensive medicine theory defies conclusive evaluation because it ultimately rests on divining the private thoughts underlying doctors’ decisions. But broad trends over time provide convincing evidence that the defensive medicine theory is essentially bogus. If litigation fears truly prompt unnecessary tests and procedures, then the volume of care rendered should be declining in sync with diminished litigation risk. This thinking is at the heart of the argument for imposing caps on malpractice awards. But, as illustrated above, costs have marched upward while litigation risk has declined. Increased volume of care, including testing, is almost certainly a key reason for the increased costs.

This idea that the volume of care would decrease has to do with the fact that Texas enacted restricted litigation laws in 2003, and that while malpractice payments fell between 2003 and 2010, health care costs increased faster than the national average, especially for medicare diagnostic tests.

Well, maybe. But Texas is not solely responsible for soaring health costs.

So what DOES the report think may be the cause of rising costs?

Those truly looking to stem health care costs should look elsewhere. This report reviews the 2003 and 2013 pay for physicians in six specialties (Anesthesiology, Cardiology (noninvasive), General Surgery, Internal Medicine, Ob-Gyn and Radiology) as chronicled by Modern Healthcare in its annual doctors’ compensation survey. Practitioners of these specialties have seen their pay rise from 24.3 percent (ob-gyn) to 82 percent (radiology) over this time period. For all specialties but one, pay raises have exceeded inflation. Likewise, Modern Healthcare reports that compensation for health care system CEOs rose at more than twice the rate of inflation from 2003 to 2012 (to over $1.1 million annually, on average). Pay increases for chief medical officers and chief financial officers also far outpaced inflation. These figures suggest that financial incentives, not litigation or the fear of it, provide a far more plausible explanation for soaring costs.

You got me. I'm a greedy doctor, more interested in being out on my expensive yacht than taking care of patients.

Here's another set of figures:

WASHINGTON, D.C. Aug. 11, 2010 - Health Care for America Now (HCAN), the 1,000-member coalition that led the successful fight for health reform, released a report today showing that in 2009, ...chief executives of the 10 largest for-profit health insurance companies collected total pay of $228.1 million, up from $85.5 million the year before. The CEOs of UnitedHealth Group, WellPoint, Aetna, CIGNA, Humana, Coventry Health Care, Health Net, Amerigroup, Centene and Universal American took $944.1 million in compensation from 2000 through 2009, according to the report, entitled "Breaking the Bank."

The boldface is mine. But 228 MILLION! That's 3 orders of magnitude greater than the average physician's income. That's the kind of number that would go a long way towards defraying health care costs.

And who is "Public Citizen"? The Board of Directors includes a bunch of lawyers, a couple activists, and one stand-up comic.

I really hope they asked at least one doctor's opinion about medical malpractice.

Sunday, August 4, 2013

Just As Good

All the hype about healthcare reform and the Affordable Care Act and Obamacare reminds me of an article a friend sent me a couple years ago.

The basic idea is that you can't have more people covered and better quality of care for less money. So concessions need to be made somewhere.

The article, written by David Kent, entitled, Just-as-Good Medicine, and published in American Scientist, March/April 2010 issue, is not only informative, it's extremely well-written and entertaining. Please read it.

And here's the first paragraph, to whet your appetite:

The rabbi’s eulogy for Sheldon Kravitz solved a minor mystery for my father: what was behind the odd shape of the juice cups he had been drinking from after morning services for the last few years? Adding a bit of levity while praising his thrift and resourcefulness, the rabbi told of how Sheldon purchased, for pennies on the dollar, hundreds of urine specimen cups from Job Lot, that legendary collection of pushcarts in lower Manhattan carrying surplus goods—leftovers, overproduced or discontinued products, unclaimed cargo. At the risk of perpetuating a pernicious cultural stereotype, for men of my father’s generation like Sheldon, raised during the Great Depression, bargain hunting was a contact sport and Job Lot was a beloved arena. My father, too, would respond to the extreme bargains there with ecstatic automatisms of purchasing behavior and come home with all manner of consumer refuse, including, and to my profound dismay, sneakers that bore (at best) a superficial resemblance to the suede Pumas worn and endorsed by my basketball idol, the incomparably smooth Walt “Clyde” Frazier. My father would insist that such items were “just as good” as the name brands. But we, of course, knew what “just as good” really meant.

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Who Needs Who

Check out this article in Psychiatric News, if you haven't already.

Jeffrey Lieberman, president of the APA, asks us to be nice to poor, little Big Pharma.

He notes past problems, "including high drug prices, aggressive marketing practices and direct-to-consumer advertising, efforts to buy influence with physicians, and, perhaps most egregiously, the suppression of data on drugs’ dangerous side effects."

He goes on to say:

But let’s face it, they need us and we need them. We must recognize the important, beneficial role that drug companies have long played in all areas of medicine. While not minimizing problems, we simultaneously must remember how products have improved the quality of health care and quality of life in our society, and their funding has helped to advance research, public outreach, and training.

He finishes up with:

We now are moving forward with careful vigilance in ways that recognize the value of industry relationships. Under the auspices of the American Psychiatric Foundation (APF), interactions with industry are helping to restore important relationships. ...I believe that the rules and models for informational, educational, and research engagement can and should be developed and applied in ways that allow for our optimal engagement with companies. Doing so would not only help us learn from the mistakes of the past; it would help us improve the future for our profession and our patients.

I agree with the fact that we need them. Unless we want to put all our patients on Lithium and St. John's Wart, the meds have to come from someplace. And I don't fault Big Pharma for trying to make a buck or two billion.

But I also agree with the fact that they need us. No prescribers, no sales. So why do we have to be nice to them? And why does the president of the APA have to ask us to do so?

Sorry if I'm skeptical, but:

GlaxoSmithKline has admitted that some of its senior Chinese executives broke the law in a £320m cash and sexual favours bribery scandal.

And:

Big pharma mobilising patients in battle over drugs trials data.

The veracity of this last one is a little controversial, I suspect because Big Pharma intervened (See Eye For Pharma).

The idea is that if pharmaceutical companies make their data transparent for review and interpretation by the world at large, like in RIAT, science may be compromised, and private patient information may be revealed.

I guess the world at large doesn't understand science as well as pharmaceutical companies do. And oh yeah, data for subjects in drug trials are anonymous.

(Please check out 1boringoldman.com for a more extensive discussion of this controversy)

So, again, why is the APA on a kick to endorse Big Pharma?

To quote Danaerys Targaryen, "I am only a young girl, and know little of such matters."

But I wonder what the APA gets out of the endorsement.

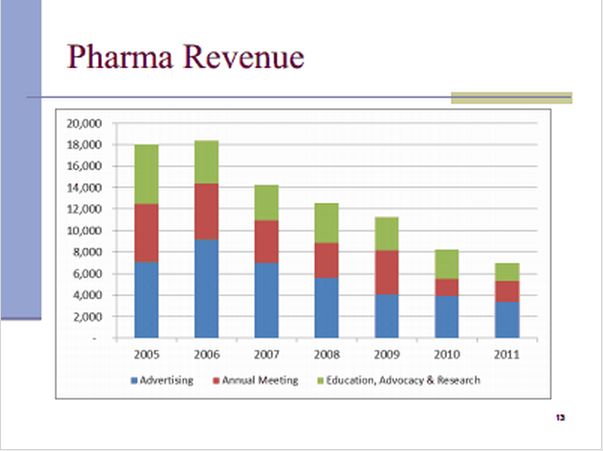

According to Gary Greenberg, regarding the APA's financial picture:

Income from the drug industry, which amounted to more than $19 million in 2006, had shrunk to $11 million by 2009, and was projected to fall even more. Membership was dropping, off by nearly 15% from its highs, and with it income from dues and attendance fees. Journal advertising was off by 50% from its 2006 high of $10 million.

I looked up the APA's 2012 Treasurer's Report, and found the following charts:

What's a picture worth, again?

Jeffrey Lieberman, president of the APA, asks us to be nice to poor, little Big Pharma.

He notes past problems, "including high drug prices, aggressive marketing practices and direct-to-consumer advertising, efforts to buy influence with physicians, and, perhaps most egregiously, the suppression of data on drugs’ dangerous side effects."

He goes on to say:

But let’s face it, they need us and we need them. We must recognize the important, beneficial role that drug companies have long played in all areas of medicine. While not minimizing problems, we simultaneously must remember how products have improved the quality of health care and quality of life in our society, and their funding has helped to advance research, public outreach, and training.

He finishes up with:

We now are moving forward with careful vigilance in ways that recognize the value of industry relationships. Under the auspices of the American Psychiatric Foundation (APF), interactions with industry are helping to restore important relationships. ...I believe that the rules and models for informational, educational, and research engagement can and should be developed and applied in ways that allow for our optimal engagement with companies. Doing so would not only help us learn from the mistakes of the past; it would help us improve the future for our profession and our patients.

I agree with the fact that we need them. Unless we want to put all our patients on Lithium and St. John's Wart, the meds have to come from someplace. And I don't fault Big Pharma for trying to make a buck or two billion.

But I also agree with the fact that they need us. No prescribers, no sales. So why do we have to be nice to them? And why does the president of the APA have to ask us to do so?

Sorry if I'm skeptical, but:

GlaxoSmithKline has admitted that some of its senior Chinese executives broke the law in a £320m cash and sexual favours bribery scandal.

And:

Big pharma mobilising patients in battle over drugs trials data.

The veracity of this last one is a little controversial, I suspect because Big Pharma intervened (See Eye For Pharma).

The idea is that if pharmaceutical companies make their data transparent for review and interpretation by the world at large, like in RIAT, science may be compromised, and private patient information may be revealed.

I guess the world at large doesn't understand science as well as pharmaceutical companies do. And oh yeah, data for subjects in drug trials are anonymous.

(Please check out 1boringoldman.com for a more extensive discussion of this controversy)

So, again, why is the APA on a kick to endorse Big Pharma?

To quote Danaerys Targaryen, "I am only a young girl, and know little of such matters."

But I wonder what the APA gets out of the endorsement.

According to Gary Greenberg, regarding the APA's financial picture:

Income from the drug industry, which amounted to more than $19 million in 2006, had shrunk to $11 million by 2009, and was projected to fall even more. Membership was dropping, off by nearly 15% from its highs, and with it income from dues and attendance fees. Journal advertising was off by 50% from its 2006 high of $10 million.

I looked up the APA's 2012 Treasurer's Report, and found the following charts:

What's a picture worth, again?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)