Study Finds Long-Term Benefits of CBT for Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression

Patients with treatment-resistant depression who receive cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in addition to antidepressants over several months may continue to benefit from the therapy years later, according to a study in Lancet Psychiatry...

“Our findings provide robust evidence for the effectiveness of CBT given as an adjunct to usual care that includes medication in reducing depressive symptoms and improving quality of life over the long term,” the study authors wrote. “As most of the CoBalT participants had severe and chronic depression, with physical or psychological comorbidity, or both, these results should offer hope for this population of difficult-to-treat patients.”

You can link to the Lancet Study, Long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in primary care: follow-up of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial, by Wiles et al, here. It's full text.

In brief:

Background

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for people whose depression has not responded to antidepressants. However, the long-term outcome is unknown. In a long-term follow-up of the CoBalT trial, we examined the clinical and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to usual care that included medication over 3–5 years in primary care patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Methods

CoBalT was a randomised controlled trial done across 73 general practices in three UK centres. CoBalT recruited patients aged 18–75 years who had adhered to antidepressants for at least 6 weeks and had substantial depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI-II] score ≥14 and met ICD-10 depression criteria). Participants were randomly assigned using a computer generated code, to receive either usual care or CBT in addition to usual care. Patients eligible for the long-term follow-up were those who had not withdrawn by the 12 month follow-up and had given their consent to being re-contacted. Those willing to participate were asked to return the postal questionnaire to the research team. One postal reminder was sent and non-responders were contacted by telephone to complete a brief questionnaire. Data were also collected from general practitioner notes. Follow-up took place at a variable interval after randomisation (3–5 years). The primary outcome was self-report of depressive symptoms assessed by BDI-II score (range 0–63), analysed by intention to treat. Cost-utility analysis compared health and social care costs with quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs)...

They took an old study, with subjects who had taken antidepressants for at least 6 weeks and had substantial depression symptoms characterized by a BDI-II score of at least 14, and followed up with a questionnaire and GP notes. Primary outcome was self-report of depressive symptoms assessed by BDI-II score. They also did a cost analysis.

Findings

Between Nov 4, 2008, and Sept 30, 2010, 469 eligible participants were randomised into the CoBalT study. Of these, 248 individuals completed a long-term follow-up questionnaire and provided data for the primary outcome (136 in the intervention group vs 112 in the usual care group). At follow-up (median 45·5 months [IQR 42·5–51·1]), the intervention group had a mean BDI-II score of 19·2 (SD 13·8) compared with a mean BDI-II score of 23·4 (SD 13·2) for the usual care group (repeated measures analysis over the 46 months: difference in means −4·7 [95% CI −6·4 to −3·0, p<0·001]). Follow-up was, on average, 40 months after therapy ended. The average annual cost of trial CBT per participant was £343 (SD 129). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was £5374 per QALY gain. This represented a 92% probability of being cost effective at the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence QALY threshold of £20 000.

Follow-up was a median of 45.5 months, at which point, the CBT group had a mean BDI-II of 19.2, and the control group a mean BDI-II of 23.4

Interpretation

CBT as an adjunct to usual care that includes antidepressants is clinically effective and cost effective over the long-term for individuals whose depression has not responded to pharmacotherapy. In view of this robust evidence of long-term effectiveness and the fact that the intervention represented good value-for-money, clinicians should discuss referral for CBT with all those for whom antidepressants are not effective.

Note that "individuals whose depression has not responded to pharmacotherapy," were taking antidepressants for 6 weeks. The study states later that, "This definition of treatment-resistant depression was inclusive and directly relevant to primary care."

Let's look at the details. I'll start by stating that I'm not going to consider the cost effectiveness, because I don't know how. And it may be that even if the clinical effects turn out to not be impressive (spoiler!), the treatment may be worthwhile from a financial standpoint.

At the start of the current study, all patients were taking antidepressants, and were randomized to 12-18 sessions of CBT, or usual care from their GPs. I find this confusing. It seems like medication ought to be a confounder, since depression is cyclic to begin with and people respond to medications at variable rates. Also, if you consider these patients to be treatment resistant, why continue them on antidepressants?

I also find what they did with the outcome measures confusing:

The primary outcome was self-report of depressive symptoms assessed by BDI-II score (range 0–63). Secondary outcomes were response (≥50% reduction in depressive symptoms relative to baseline); remission (BDI-II score <10); quality of life (Short-Form health survey 12 [SF-12]); and measures of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (Generalised Anxiety Disorder assessment 7 [GAD-7])...

The primary outcome for the main trial was a binary response variable; for this follow-up, the primary outcome was specified as a continuous outcome (BDI-II score) to maximise power. The change in the specification of the primary outcome for the long-term follow-up was made at the time the request for additional funding was submitted to the funder (Nov 6, 2012).

Does this mean they changed the primary outcome? In the original CoBalT trial, "The primary outcome was response, defined as at least 50% reduction in depressive symptoms (BDI score) at 6 months compared with baseline." Did the present study start out using response, and then switch to change in BDI-II score after the fact, which we all know is a no-no? They're claiming they changed it when they requested funding for the current study, but is that before or after they had established their primary outcome measure?

Or did the current study start with change in BDI-II score as the primary outcome measure, and is that okay? In other words, if you're basing your current study on a previous study, is it valid to establish your protocol with a different outcome measure than the original study? I don't know.

Moving on. The study makes a lot of claims about secondary outcomes, and whether or not subjects were still taking antidepressants, but I'm restricting myself to thinking about the primary outcome, and the BDI-II measures are as follows:

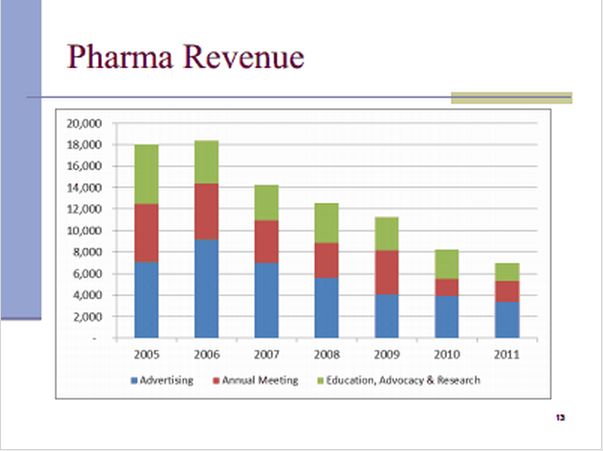

The effect size, according to this chart, is 0.45, which is on the low side of moderate. I don't know how they did their computation, but when I used 1BoringOldman's spreadsheet (see this post), I got a Cohen's d effect size of 0.31, which is low.

I'm not sure how this constitutes "Robust evidence." I'm also not sure what's robust about a mean BDI-II of 19.2, when by their definition, a BDI-II score of more than 14 is considered "Substantial depressive symptoms."

Look. I'm not a big fan of CBT, but I'm willing to consider it as a useful treatment if you show me good data. Just don't go hyping your at-best-mediocre data like it's amazing. But of course, Psychiatric News is a product of the APA.